Mind-Body Surfing On A Psychic Tsunami

M'Lady and I met Adam Purple and visited the Garden of Eden in the early 1980's. I always admired his urban pioneer spirit as well as his ability to bring beauty and order out chaos and destruction. You can see more pictures of the garden and Adam here.

He was an original and a character of the first order.

February 22, 1998

Adam Purple's Last Stand

Adam Purple's Last Stand

By JESSE MCKINLEY

IT'S a bright Sunday morning and the sole resident of 184 Forsyth Street, a small, spry man with a long gray beard, is in his backyard performing his most cherished ritual.

''This ground is all handmade,'' he says, crouching over a shallow pit and slowly tipping several cans of ash, sawdust, food scraps and his night soil into the earth. He replaces the bricks that cover his pit, then scoffs at the city officials whose plans may well put an end to his special means of making compost.

''They're going to come destroy this?'' he says. ''By what right?''

His name, at least most of the time, is Adam Purple, and since 1981 he has lived on the ground floor of No. 184, an abandoned city-owned building on the Lower East Side, without electricity, without heat, without indoor plumbing.

His endurance is impressive when you consider Mr. Purple's age -- 67 -- and the other elements of his ascetic regimen. He is a strict vegetarian, fueling himself with a tofu-based stew he makes once a week over his wood-burning stove. He collects his water from fountains and open hydrants and then stores it in jugs in his ever-cool basement. He eschews petroleum products and the machines that consume them, from oil lamps to city buses.

He scavenges most everything he needs on the streets, he says, from his gray tennis shoes to wood for his stove to batteries for the flashlights he uses after dark. And the cans and bottles he collects and recycles earn him about $2,000 a year, money he uses for two extravagances: a phone and a daily cup of coffee.

What's driving him?

''One doesn't have to be a conspiracy theorist or a doomsayer to recognize that there may be something happening to the atmospheric systems on the planet Earth,'' Mr. Purple said. ''That's why I renounce the flush toilet, renounce the internal combustion engine. As a political statement. I can live without.''

This ecological ethos led to Mr. Purple's most noted accomplishment -- and his animus toward all things bureaucratic. In the mid-1980's, Mr. Purple was at the center of a bitter fight over his Garden of Eden, an elaborate and widely praised community garden he cultivated on five vacant city-owned lots behind his building.

The city wanted to build low- and moderate-income housing there. The battle drew international attention and the scrutiny of the Federal courts. In January 1986, the city finally bulldozed the garden; several low-rise apartment buildings were put up on the site.

Now, Mr. Purple is fighting the city again, this time over a plan to demolish 184 Forsyth, a decaying six-story tenement, and replace it with a 21-unit federally funded housing project sponsored by the New York Society for the Deaf. Mr. Purple thinks the building should be renovated, preferably with an apartment for him.

Community Board 3 is to vote Tuesday on the demolition plan. But the final decision lies with the City Council, and there, Mr. Purple's prospects seem slim. ''No one wants to displace people,'' said Councilwoman Kathryn E. Freed. ''But you can hardly quarrel with the need of housing in his city.''

Even Mr. Purple's supporters say his blocking the project is a long shot. But his latest campaign has codified his reputation as an ornery gadfly, a man whose quixotic struggles seem focused not only on defending his turf but also on maintaining a life style and ideals that, for many, went out of style with the Nixon Administration.

''He is the purest example of a hippie ever seen in this city,'' said Mary Cantwell, the author of ''Manhattan, When I Young,'' who met Mr. Purple in 1985. ''He is an artifact of that era, living in a very unlikely time and place, namely present-day New York City.''

Mr. Purple has been something of a fringe fixture ever since he moved to the city 30 years ago. His appearance and his moniker were striking even in a city known for its eclectic characters and wild sartorial tastes. During much of the 70's and early 80's, he dressed almost entirely in the royal hue: purple shirts, purple sweaters, purple pants. With his beard, gray hair, floppy green stocking cap, sunglasses and twinkling blue eyes, he looks like Santa Claus if Santa hit the skids and lost the belly.

He moved into 184 Forsyth in 1972 as a month-to-month tenant. In 1976, the building was abandoned by its landlord and later transferred to the city. Its last tenants -- all but Mr. Purple -- left after Consolidated Edison turned off the electricity in 1981 because the city had not paid the bill.

Mr. Purple says he hasn't paid rent since the landlord left and services ceased, and city records show he owes some $350,000 in back rent, unlikely to be paid anytime soon. ''Those pinheads,'' Mr. Purple said recently in typical fashion. ''Don't they know who they're dealing with?''

Mr. Purple has staved off at least four attempts to evict him, said his lawyer, Colleen McGuire. Three eviction proceedings were dismissed on technicalities; the fourth has been pending for nearly a decade, effectively killing the case, Ms. McGuire said.

The city's Department of Housing Preservation and Development released two statements this month supporting the deaf project and saying they would try to to settle with Mr. Purple. But a spokesman, Rick Lepkowski, declined to discuss specifics.

Mr. Purple, meanwhile, says he works hard to keep up the building, putting makeshift caps on several chimneys and spending $3,500 for a new roof. ''The issue is not Adam Purple, the issue is this building,'' he said, pointing at its ragged exterior and shattered windows. ''The issue is malicious neglect, and this is the evidence.''

For some observers, there is more at stake than where Mr. Purple lives. It is what he represents: a kind of radical individualism that thrived on the Lower East Side long before the musical ''Rent!'' made squatters fashionable and trendy clubs began sprouting on gritty side streets.

''It seems what he's trying to preserve is really himself, and that's a cause that deserves some support,'' said James Stewart Polshek, the former dean of the School of Architecture at Columbia University, who called the destruction of the Garden of Eden ''an urban crime.'' ''He's more important than the bricks and mortar.''

While his place in the pantheon of the city's eccentrics is secure, Mr. Purple remains an elusive public figure. Nobody seems sure of his real name. Over the years he has assumed pseudonyms ranging from the clever (the Rev. Les Ego) to the historical (John Peter Zenger 2d) to the just plain odd (General Zen of the Headquarters Intergalactic of Psychic Police of Uranus). A database search of the Social Security number listed for Mr. Purple on a 1982 city document found it registered to a man born in North Carolina in 1978.

What Mr. Purple reveals of his history suggests a life colored by both a traditional American upbringing and a countercultural awakening. He was born and raised in Independence, Mo., one of seven children. His father, Richard, was a machinist; his mother, Juanita, a seamstress.

Two jarring episodes marked his early life. When he was 9, he said, his 11-year-old brother died of appendicitis because ''the doctors wouldn't operate on him until my father got there with money.''

Two jarring episodes marked his early life. When he was 9, he said, his 11-year-old brother died of appendicitis because ''the doctors wouldn't operate on him until my father got there with money.''

Three years later, his father was accidentally electrocuted fighting a fire at the machine shop while his son Adam looked on. ''That's another reason I don't need electricity,'' Mr. Purple said.

He says he attended a small college in Kansas and served two years stateside in the United States Army before returning to school for a master's degree in journalism from the University of Missouri. After several years teaching at high schools and junior colleges in California and South Dakota, Mr. Purple said, he made his way East, working briefly for a political action group run by Paul Krassner, the satirist, and then landing a job as a reporter for The York Gazette and Daily in York, Pa.

He says he attended a small college in Kansas and served two years stateside in the United States Army before returning to school for a master's degree in journalism from the University of Missouri. After several years teaching at high schools and junior colleges in California and South Dakota, Mr. Purple said, he made his way East, working briefly for a political action group run by Paul Krassner, the satirist, and then landing a job as a reporter for The York Gazette and Daily in York, Pa.

It was there, working the police beat, Mr. Purple says, that he began to feel distanced from the mainstream. ''It taught me to be wary of the police,'' he said. ''They had dogs and they used them on people.''

He left Pennsylvania. During the mid-1960's, he traveled, he said, finding kindred spirits in hippie havens like Berkeley and Big Sur, in California, and Dixon, N.M., experimenting with drugs and writing.

In 1968, he landed in New York, hoping to get a book contract for the volume of meditation games he called ''Zentences!'' While he never found a publisher, Mr. Purple says, he made some 600 copies of the book between 1967 and 1973. One copy, measuring one inch by one inch, is currently safeguarded as a historical artifact in the New York Public Library's rare book collection.

The Village Voice was the first publication to notice Mr. Purple, with a report in June 1969 of ''a bearded bon vivant'' who hung out in Central Park, called himself Les Ego and put ''people on his back to 'blow their minds and straighten their spines.' ''

Though Mr. Purple sometimes calls himself ''an old reporter'' and keeps careful records of all the articles ever published about him, he remains extremely skeptical of the press. In 1990, a reporter from New York magazine requested an interview for a ''Where Are They Now?'' article. Mr. Purple sent back a copy of the reporter's letter with its grammar corrected.

''Please allow me to respond to your somewhat inept note,'' he wrote, under the Les Ego pseudonym. ''Because New York has published nothing zenlightening about the Garden since 27 August 1979, I see no reason to trust your magazine.''

Reporters who do manage to interview Mr. Purple typically have their published work mailed back to them with corrections, factual and interpretive, penned in the margins. Photographers are told how, where and sometimes even with what lens to shoot.

He reads voraciously, spending much of each day perusing journals like the World Press Review and Foreign Affairs, or digging into the 3,000 books he stores throughout the building. A recent visitor noticed copies of The New York Observer, Time Out magazine and Vanity Fair lying inside the front door, some addressed to fictional characters of Mr. Purple's invention.

On the third floor are his archives, a collection of press clips and personal writings stored on long hand-made tables and covered with old newspapers to protect them from the occasionally leaky roof.

Anyone looking for a simple answer or a sound bite from Mr. Purple is likely to be frustrated. Conversations with him travel in immensely wide, long arcs. He quotes freely -- and accurately -- from Socrates, Shakespeare and Bob Dylan, and finds connective tissue between such topics as the ozone layer, the irrationality of pi and the relation between his garden and the black monolith from the movie ''2001: A Space Odyssey.''

''What makes him interesting is that he's not a nut,'' Mr. Polshek said. ''He likes to pretend he is, but he's one smart cookie.''

Also, it quickly becomes apparent, his mind runs in circular currents, and the destruction of the Garden of Eden is an eddy that often traps his thoughts. ''It was my pursuit of happiness,'' he said. The current threat to his building only increases its pull.

The Garden began in the spring of 1975. Forsyth Street, like much of the Lower East Side, had fallen into a spiral of urban decay, with prostitution, drug use and trash-strewn lots marring a strip once known for vibrant storefronts and sturdy old tenements. With the city suffering a financial crisis, vacant buildings in the area were often demolished to prevent arson and other crimes.

One building torn down was directly behind the back windows of the apartment of Mr. Purple and his companion at the time, a young woman who went by the name of Eve. They decided to plant something, said Mr. Purple, in part to attract crickets, which he said would warn them if someone was approaching their back window. ''You can't get within three feet of a cricket without it stopping its chirping,'' he said. ''It's silence as a security system.''

He began biking to Central Park to collect horse manure, which he then mixed with ash, his own waste, and with rubble in the lot to create batches of fertile topsoil. That process alone attracted attention.

''He'd pull up every so often on his way back from the park, with a full load,'' said Seymour Hacker, a rare books dealer on West 57th Street and Mr. Purple's friend. ''It was quite a vision for my customers.''

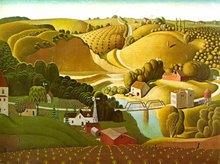

Planted in perfect concentric circles around a yin-yang symbol, the garden slowly grew outward into neighboring lots, becoming a majestic 15,000-square-foot array of raspberries, roses, lilies, fruit trees and other flora, all diligently tended by Mr. Purple and his supporters.

The garden drew local admirers and global press. National Geographic did a photo spread, as did several foreign publications. Mr. Purple's work drew comparisons to the earth sculpture of artists like Robert Smithson and Walter De Maria.

''It was an absolutely astonishing creation,'' said Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblet, an expert on street life and a former head of New York University's Department of Performance Studies. Besides its natural beauty, Ms. Kirshenblatt-Gimblet said, the garden had an inherently political message.

''He made a garden out of a ruin,'' she said. ''So symbolically it was an especially strong indictment of the failure of the city to do the same.''

But by the early 1980's, city officials were looking for places to build housing for some half-million people. One site they had in mind was that of the garden.

As the demolition date approached, opposition grew. Neighborhood activists and supporters swarmed into community board meetings and the garden's brick paths. Painted purple footprints began appearing on sidewalks, wending their way to the garden. A group of architects, academics and environmentalists went to court to block construction.

In 1985, Judge Vincent L. Broderick of Federal District Court, who had previously barred the garden's demolition, ruled that ''irreparable harm would be incurred only by Purple were the garden to be destroyed since few others derive benefit from it.''

On Jan. 8, 1986, as Adam Purple watched from his windows, bulldozers uprooted the Garden of Eden. ''I gave this city two works of art,'' said Mr. Purple, referring to the garden and his book. ''They ignore one and trash the other.''

He added, with a pinch in his voice: ''Give me a break. When do I get respect?''

In response to questions about the current conflict, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development issued a statement saying that it and the Society for the Deaf were willing to help Mr. Purple find another apartment. ''But he has not been amenable,'' the statement said.

Considering Mr. Purple's cantankerous nature, that may be an understatement. He is certain that those who demolished his garden -- or who destroy 184 Forsyth -- will have a cosmic comeuppance.

In response to questions about the current conflict, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development issued a statement saying that it and the Society for the Deaf were willing to help Mr. Purple find another apartment. ''But he has not been amenable,'' the statement said.

Considering Mr. Purple's cantankerous nature, that may be an understatement. He is certain that those who demolished his garden -- or who destroy 184 Forsyth -- will have a cosmic comeuppance.

''The mills of the gods grind slowly,'' he said with a sly smile, paraphrasing a quotation whose author he has forgotten. ''But they grind exceedingly fine.''

In the meantime, Mr. Purple sticks to a regular routine, waking at dawn, redeeming his cans, meditating or reading in the afternoon. His building is chilly and damp inside. In the front hallway, amid dozens of scavenged umbrellas, the plaster has begun to slip from the ceiling. At the end of the hall is what Mr. Purple calls his ''inner sanctum,'' two rooms adorned with his wood stove, a typewriter, a mattress on the floor, and a pair of enamel kettles he uses as chamber pots. On cold days, he is a slave to his fire, stoking its embers early in the morning and feeding it scavenged wood all day long.

At night, he stows away his reading and turns on a small radio to listen to the news and opinion on WBAI-FM, a longtime bastion of liberal die-hards. Depending on the cold, he might wear a scarf or gloves to bed.

All that remains of the garden is a single Chinese empress tree, a few transplanted black raspberry bushes and, in his kitchen, some dried basil he uses to season his stew.

Mr. Purple wears little purple nowadays, except the ball cap under his stocking cap. He put the color away, he said, after the garden was destroyed.

''Purple went out with the garden,'' he said. ''Adam Purple doesn't exist.''

He said he might consider taking an apartment if the city offered it, but only if he could continue his ritual of turning waste into soil. And, of course, he'd have a few questions. ''How come I'm being given preference?'' he said. ''How can I be put at the top of the list?''

Why wouldn't he leave the city, he is asked, go someplace where the climate --

both human and celestial -- is more in tune with his horticultural urges?

Mr. Purple harrumphs. ''I'm teaching lessons about how to survive, an experiment on making earth,'' he says. ''Of course you could do it outside the city, but the challenge is here.''

both human and celestial -- is more in tune with his horticultural urges?

Mr. Purple harrumphs. ''I'm teaching lessons about how to survive, an experiment on making earth,'' he says. ''Of course you could do it outside the city, but the challenge is here.''

He pauses for a second, and then, as is his way, reconsiders. ''It's the Athenian oath,'' he said. ''The Athenian oath. The duty or responsibility of every citizen to leave the scene a little better than when they got there, to improve things.''

A Rare, Classic Volume, All One Square Inch of It

Deep within the New York Public Library's rare book collection, there is an old wood cabinet where the some of the world's tiniest works of literature sit under lock and key.

The collection includes a 1660 edition of a shorthand Bible (2 1/2 inches tall) and a 19th-century copy of a letter by Galileo that measures a whopping 1/2 inch by 3/4 inch. Then there is a more recent addition: ''Zentences!'' by Les Ego, also known as Adam Purple.

The book, donated by Mr. Purple in 1972, has been preserved because of its quality and because of its author's historical significance, John Rathe, a librarian, said. It measures one inch by one inch. Besides its size, the structure and content of ''Zentences!'' are also curious. Each tiny page is split in two. On the top are nouns like ''Love'' or ''The Tao.'' On the bottom are verb phrases, for example, ''needs a vacation in Oz'' and ''is a chaste shadow.''

The idea, Mr. Purple said, was that a reader could flip through the book and pair the nouns with the verbs to create koan-like sentences for meditation. Hence the title.

Its trippy concept notwithstanding, ''Zentences!'' is precisely crafted, with a cloth cover, dyed page edges, headbands on the binding and an inscription page. ''This is not an art object pretending to be a book,'' Mr. Rathe said. ''It is, in fact, a book made in classic fashion.''

Mr. Purple says that he hand-made some 600 copies, each with different words but that probably fewer than 100 existed today.

Mr. Purple says that he hand-made some 600 copies, each with different words but that probably fewer than 100 existed today.

''People left them in their pants and they got washed away,'' he says. ''But the ones that are still around are going to be worth a lot someday.'' JESSE McKINLEY

No comments:

Post a Comment